Imagine: Through a genetic test you can find out whether or not you carry the gene for a rare, incurable disorder. This disorder, should you possess the triggering gene, will cause your body to wither and die when you reach a particular age, 28, 36, 44, or what have you. Would you take that test? Would you want to know? Would you not want to know?

Say you do take that test. You do not possess the triggering gene, so your body will not wither and die as described above. However, you carry the recessive gene, which, should you partner with another carrier of the recessive gene, may be present in your offspring as the triggering gene. You may have a child who you know will not live beyond a certain age. Do you even risk having such a child?

***

One day he asked himself:

"If suddenly a cure for diabetes were available, would you take it?" . . . "How does he answer this question?"

What was his first impulse? To say Yes?

"He doesn’t remember what his first impulse was."

Did he answer No?

"He did answer No, after a time."

Why did he answer No to a cure for diabetes?

"He has no answer for Why. It is inexplicable and complex. This is not an easy question. At a later stage of life, he is likely to die from diabetes complications."

Yes, he is. So even if a cure were available, you would not take it?

"No. He is okay with it. He accepts what he will have to face."

That's easy for him to say now. He may feel differently twenty years down the road.

"Stop talking, please."

2009/05/26

Question for an Alternate Future

What Are You Talking About?

question,

reflection,

subcutaneous punctuation

My Critical Introduction: A Young Draft

This is a reflection on process. The writing process in general, and the process of writing this collection. They are one and the same. I have neither time nor patience nor space to offer comfort, encouragement, good cheer, or humorous anecdotes. Writing is an obsession both time- and mind-consuming. Little else provokes more aggravation. That is what you will find here: aggravation. There are no comfort zones. Those who write from comfort address only their ego, and egos love attention.

Once you have written all your stories (or poems, essays, etc.), you start again, and write anew. Those who write for awhile and then give up are left with resources they haven’t helped to destroy. Material (or Subject Matter) is used up, re-used, always-already destroyed and regained, reprocessed. Everything has been done. Nothing has not been left undone. This is very simple to understand. Stretching for pure originality in writing dooms you to frustration, at best; failure, at worst. If you have something to write, then write it. If you believe you have nothing to write, or nothing new to write, then you won’t write a word. And that’s okay with me.

I will focus on story-writing process. Stories require two basic attributes: Spine and Heart. First comes Spine, the logical structure (or framework) of sense. A story without a Spine is nonsense: when you read a Spineless story, you become lost, confused, frustrated, aggravated, annoyed, or so thoroughly amused by the bad writing that you will never again bother to read that particular author’s work.

Spineless stories have these and possibly other qualities: Character behavior seems unbelievable, ridiculous, absurd. Events happen for little or no apparent reason. Abstractions abound. Narrative focuses on redundancies, irrelevancies, everyday tediums. Narrative time runs out of control. The text contains numerous and obvious typos, glitches, unnecessary verb tense shifts, misspellings, and the like. When you read it, you have no idea what is going on.

I think of a story as a human body. Without a Spine, the body is paralyzed, almost useless. The human body cannot function without a Spine. (Stories do not have the luxury of wheelchairs, respirators, or physical therapists.) The human body can survive without arms and legs, without hair, without eyes, without a tongue, without sex organs; the human body can survive with only half of one lung, or with one half-functional kidney. But a Spine is a requirement. The Story’s text must be clear, without glitches or typos or bizarre constructions of grammar. The Story needs to make sense when read; characters can do things that make no sense, but in ways that make sense to the reader. Nouns and Verbs make sense to the reader. Simple sentence structures make sense to the reader. Stout Anglo-Saxon words make sense to the reader. Concrete images hold the reader’s attention. Clearly delineated time keeps track of events, and reinforces the sense of a world with laws and rules. The reader should not need to pause (to look up some obscure Latinate word, to computate a pile of adjectival phrases, to translate misspellings and other grammatical glitches). When the reader can read through without stopping, and afterward knows at minimum what is going on in the Story, then the Story has a functioning Spine.

The presence of a functioning Spine makes a story, but not a good story. The best stories have not only Spine, but Heart.

[Forthcoming: Heart . . .]

Once you have written all your stories (or poems, essays, etc.), you start again, and write anew. Those who write for awhile and then give up are left with resources they haven’t helped to destroy. Material (or Subject Matter) is used up, re-used, always-already destroyed and regained, reprocessed. Everything has been done. Nothing has not been left undone. This is very simple to understand. Stretching for pure originality in writing dooms you to frustration, at best; failure, at worst. If you have something to write, then write it. If you believe you have nothing to write, or nothing new to write, then you won’t write a word. And that’s okay with me.

I will focus on story-writing process. Stories require two basic attributes: Spine and Heart. First comes Spine, the logical structure (or framework) of sense. A story without a Spine is nonsense: when you read a Spineless story, you become lost, confused, frustrated, aggravated, annoyed, or so thoroughly amused by the bad writing that you will never again bother to read that particular author’s work.

Spineless stories have these and possibly other qualities: Character behavior seems unbelievable, ridiculous, absurd. Events happen for little or no apparent reason. Abstractions abound. Narrative focuses on redundancies, irrelevancies, everyday tediums. Narrative time runs out of control. The text contains numerous and obvious typos, glitches, unnecessary verb tense shifts, misspellings, and the like. When you read it, you have no idea what is going on.

I think of a story as a human body. Without a Spine, the body is paralyzed, almost useless. The human body cannot function without a Spine. (Stories do not have the luxury of wheelchairs, respirators, or physical therapists.) The human body can survive without arms and legs, without hair, without eyes, without a tongue, without sex organs; the human body can survive with only half of one lung, or with one half-functional kidney. But a Spine is a requirement. The Story’s text must be clear, without glitches or typos or bizarre constructions of grammar. The Story needs to make sense when read; characters can do things that make no sense, but in ways that make sense to the reader. Nouns and Verbs make sense to the reader. Simple sentence structures make sense to the reader. Stout Anglo-Saxon words make sense to the reader. Concrete images hold the reader’s attention. Clearly delineated time keeps track of events, and reinforces the sense of a world with laws and rules. The reader should not need to pause (to look up some obscure Latinate word, to computate a pile of adjectival phrases, to translate misspellings and other grammatical glitches). When the reader can read through without stopping, and afterward knows at minimum what is going on in the Story, then the Story has a functioning Spine.

The presence of a functioning Spine makes a story, but not a good story. The best stories have not only Spine, but Heart.

[Forthcoming: Heart . . .]

2009/05/21

2009/05/20

Eine Schlange ist durch den Holzhaufen geschlängelt

"A snake slithered through the woodpile."

Today. A few hours ago. From the bathroom window I saw a snake, about the length of my forearm, slither into view from under the porch. It crept along, over the dwindling woodpile. I got my daughter and we watched the snake from the back door, until it disappeared. The snake was black, with yellow racing stripes along the length of its body. Beautiful.

Today. A few hours ago. From the bathroom window I saw a snake, about the length of my forearm, slither into view from under the porch. It crept along, over the dwindling woodpile. I got my daughter and we watched the snake from the back door, until it disappeared. The snake was black, with yellow racing stripes along the length of its body. Beautiful.

2009/05/19

Reflecting on Melville’s "Moby-Dick"

I began reading Moby-Dick because, well, I wanted to read it. The first time I attempted to read this tome I only got as far as the end of Chapter III. At the time I suppose I was a far less patient reader than I am now. I thought the novel seemed too wordy, too overly descriptive, the diction too elevated, the narrator too...I don’t know what. I just stopped reading it!

Now, though, Moby-Dick holds my attention in ways I never expected. As I’ve been reading, a question has formulated from somewhere, my unconscious maybe. That question is: What can I learn about Writing from the novel Moby-Dick? If I pay close enough attention to Melville’s prose, what can I take from it? What did Melville accomplish 158 years ago that is today not only relevant but also revolutionary? fresh? original? That is, by paying enough attention, what can I learn from Melville that I can apply to my own fiction?

At first glance his narrative seems dense, somehow unapproachable. This is nonsense, of course: everything that Melville has placed into Moby-Dick he has placed for a reason. From outside sources that I’ve read regarding Melville in general and Moby-Dick in particular, the conclusion that many have drawn is that Melville was obsessed with Mystery and the Unexplainable. He struggled to enlighten his readers as to the point he tried so hard to get across: Mystery. The Unknown.

I think again of "Bartleby." Why doesn’t the narrator simply throw Bartleby out on his ass? Yeah, because to do so would be impolite somehow, or unbecoming a man of the narrator’s position, or whatever other seemingly acceptable explanation one might dream up in order to excuse the narrator for his behavior. But the true reason, whatever it may be, runs much deeper. The narrator cannot explain himself, and Bartleby certainly would never be able to explain his own behavior. No proper answer is ever given. Whoever needs a proper reason or explanation for someone else’s bizarre behavior?

He or she who has been wronged or hurt by the bizarre-acting character, that’s who.

Life does not provide answers or explanations for things. People provide answers and explanations, a constant, steady stream of them. An unceasing flow of This is why and Well, you see and Because this happened and God wills it and Shit happens and Because I don’t like you and He did it to himself and so on and so forth unto infinity.

I love characters who act so strangely and without obvious reasons for their odd behavior. I love how they cannot be explained rationally. Some characters simply demand to be witnessed, seen, experienced, discussed, analyzed, gossiped about. They draw us in, whether they mean to or not. They draw us in and stir up our lives in ways that we may not like. Such characters make life more interesting. They make narrative life more interesting. I think of a Calvin & Hobbes strip, wherein Calvin has been playing musical instruments in bed, in the middle of the night. His mom is leaning into his room, half-asleep, and Calvin says, "Geez, I gotta have a reason for everything?"

Characters who raise a racket in the dead of night mean to provoke us, and their reasons are their own. We are not privy to them. I am okay with this.

As I said above, Melville placed everything in Moby-Dick for a reason. Everything points forward, into the depths of the novel where I have yet to plumb...

...Also, I like saying "Moby-Dick" over and over. And perhaps people searching for porn via google will be directed to my post, read it, and decide to give old Moby-Dick a try. Why not?

Now, though, Moby-Dick holds my attention in ways I never expected. As I’ve been reading, a question has formulated from somewhere, my unconscious maybe. That question is: What can I learn about Writing from the novel Moby-Dick? If I pay close enough attention to Melville’s prose, what can I take from it? What did Melville accomplish 158 years ago that is today not only relevant but also revolutionary? fresh? original? That is, by paying enough attention, what can I learn from Melville that I can apply to my own fiction?

At first glance his narrative seems dense, somehow unapproachable. This is nonsense, of course: everything that Melville has placed into Moby-Dick he has placed for a reason. From outside sources that I’ve read regarding Melville in general and Moby-Dick in particular, the conclusion that many have drawn is that Melville was obsessed with Mystery and the Unexplainable. He struggled to enlighten his readers as to the point he tried so hard to get across: Mystery. The Unknown.

I think again of "Bartleby." Why doesn’t the narrator simply throw Bartleby out on his ass? Yeah, because to do so would be impolite somehow, or unbecoming a man of the narrator’s position, or whatever other seemingly acceptable explanation one might dream up in order to excuse the narrator for his behavior. But the true reason, whatever it may be, runs much deeper. The narrator cannot explain himself, and Bartleby certainly would never be able to explain his own behavior. No proper answer is ever given. Whoever needs a proper reason or explanation for someone else’s bizarre behavior?

He or she who has been wronged or hurt by the bizarre-acting character, that’s who.

Life does not provide answers or explanations for things. People provide answers and explanations, a constant, steady stream of them. An unceasing flow of This is why and Well, you see and Because this happened and God wills it and Shit happens and Because I don’t like you and He did it to himself and so on and so forth unto infinity.

I love characters who act so strangely and without obvious reasons for their odd behavior. I love how they cannot be explained rationally. Some characters simply demand to be witnessed, seen, experienced, discussed, analyzed, gossiped about. They draw us in, whether they mean to or not. They draw us in and stir up our lives in ways that we may not like. Such characters make life more interesting. They make narrative life more interesting. I think of a Calvin & Hobbes strip, wherein Calvin has been playing musical instruments in bed, in the middle of the night. His mom is leaning into his room, half-asleep, and Calvin says, "Geez, I gotta have a reason for everything?"

Characters who raise a racket in the dead of night mean to provoke us, and their reasons are their own. We are not privy to them. I am okay with this.

As I said above, Melville placed everything in Moby-Dick for a reason. Everything points forward, into the depths of the novel where I have yet to plumb...

...Also, I like saying "Moby-Dick" over and over. And perhaps people searching for porn via google will be directed to my post, read it, and decide to give old Moby-Dick a try. Why not?

2009/05/15

Code of Chivalrous Conduct

1. Honor and Defend thy Writing Time. 2. That which cannot Distract, will not. 3. Knowing before you begin to write, that which shall occupy your Writing Time, prevents you from wasting energy in Indecision. 4. Leave your Writing only for that which is essential to your needs. 5. When the Writing cannot move, cannot progress, read from that which moves you. 6. Mood is sacred. Before and during Writing Time, avoid news, websites, blogs, email. 7. Never forget: No Story [or poem, or essay] Comes in a Day. 8. Should you violate your code, you may be the only person who knows; but, that knowledge shall weigh on your conscience. 9. No subject is so taboo as not to be committed to paper. 10. Never forget your family.

2009/05/14

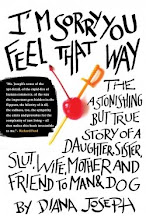

Stop All Other Activity and Read this Book

I don’t know how Wells Tower learned to write the way he does, but it’s fortunate for the rest of us that he did. His debut collection of stories, Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned, demands that once you begin reading, you do not put it down. (I might ask: Why would you put it down?) The collection begins and ends on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean. In the first story, "The Brown Coast", Bob Munroe incorrectly builds a flight of stairs in a new house. A man falls down the stairs, files a lawsuit, and Bob is fired. Then his wife finds out he’s been cheating on her. Thus the theme of self-imposed exile is set in motion: Bob moves to his uncle Randall’s fixer-upper on the tip of a small island. A neglected aquarium begins to fill with sea life that Bob fishes out of a tide pool. His wife may or may not divorce him.

In "Retreat", the narrator exiles himself to an unfinished mountaintop cabin in Maine, spending much of his time drinking with an old local named George. This is a story about brothers: Matthew, the narrator, invites his little brother, Stephen, across the country to see the mountain and the cabin, part of a continuous state of sibling rivalry.

A man’s father is forgetting his own family members and the short-term details of his life in another story. In "Leopard", you are an eleven-year-old boy who hates his stepfather with a passion. And of course the title story must be experienced for itself.

Wells Tower has a suprising eye for fresh images. The sun, in "The Brown Coast", looks "orange and slick, like a canned peach." The eighty-three-year-old narrator of "Door in Your Eye" describes what he used to write in his diary: "...when I looked back on what I wrote, I noticed I’d become like a cheap newspaperman about my life, only telling unpleasant things–-when I fought with my wife, or how much money I had given my daughter, or a time I was eating at a restaurant and a woman fell off her chair from a seizure." Tower describes a flock of geese calling to each other "in voices like nails being pulled from old boards."

I cannot do this book justice with these few meager examples. How much simpler it would be if you just read it yourself. Please do. Buy a copy new, and support this man’s writing. I hope to see another Wells Tower collection or a novel forthcoming someday soon.

In "Retreat", the narrator exiles himself to an unfinished mountaintop cabin in Maine, spending much of his time drinking with an old local named George. This is a story about brothers: Matthew, the narrator, invites his little brother, Stephen, across the country to see the mountain and the cabin, part of a continuous state of sibling rivalry.

A man’s father is forgetting his own family members and the short-term details of his life in another story. In "Leopard", you are an eleven-year-old boy who hates his stepfather with a passion. And of course the title story must be experienced for itself.

Wells Tower has a suprising eye for fresh images. The sun, in "The Brown Coast", looks "orange and slick, like a canned peach." The eighty-three-year-old narrator of "Door in Your Eye" describes what he used to write in his diary: "...when I looked back on what I wrote, I noticed I’d become like a cheap newspaperman about my life, only telling unpleasant things–-when I fought with my wife, or how much money I had given my daughter, or a time I was eating at a restaurant and a woman fell off her chair from a seizure." Tower describes a flock of geese calling to each other "in voices like nails being pulled from old boards."

I cannot do this book justice with these few meager examples. How much simpler it would be if you just read it yourself. Please do. Buy a copy new, and support this man’s writing. I hope to see another Wells Tower collection or a novel forthcoming someday soon.

2009/05/11

Limitations

Limits with which to stimulate the brains:

1. Do not use any words longer than 4 letters.

2. Do not use any words longer than 5 letters.

3. Do not use any words longer than 6 letters.

4. Do not use any words longer than 7 letters.

5. Write without using these negatives: No, Not, None, Never.

6. Write in 3rd-Person Objective perspective.

7. Have at least one character speak in rhyme.

8. Write about someone you know, but change his or her sex.

9. Write within a min-max word limit: 1000–3000 words.

10. Write from the point of view of a character who is blind.

11. Write from the point of view of a character who is deaf.

12. Write from the point of view of a character who is dead.

13. Write from the point of view of a character who is dying.

14. Write from the point of view of a character who is paralyzed.

15. Write from the point of view of a character who is confronting his/her worst fear.

16. Write without Flashback.

17. In place of Flashback, use Flashforward.

18. Write a piece set entirely in one scene. If flashback or recollection is used, they must relate to the one scene in which the piece is set.

19. Write from the point of view of a character who is severely hyperactive or who is otherwise far too overstimulated.

20. Write from the point of view of a character who talks to himself or herself.

21. Write from the point of view of a character who is trying to justify to a group of people some act that the group considers unjustifiable.

22. Use an unusual setting or environment: a wine cellar; a bomb crater; a drained swimming pool; a burning building; a hot air balloon; a railroad yard; the inside of a cargo plane; a freeway underpass; a vault full of gold bullion; a hotel room, the address of which a S.W.A.T. team has mistakenly been given.

23. Write about one or more characters procrastinating: the act of procrastination is the source of conflict.

24. Write using one or more characters who have an unusual or off-the-wall hobby.

25. Write using one or more characters who have an unusual or off-the-wall pet.

26. Write using one or more characters who have an unusual or off-the-wall obsession.

1. Do not use any words longer than 4 letters.

2. Do not use any words longer than 5 letters.

3. Do not use any words longer than 6 letters.

4. Do not use any words longer than 7 letters.

5. Write without using these negatives: No, Not, None, Never.

6. Write in 3rd-Person Objective perspective.

7. Have at least one character speak in rhyme.

8. Write about someone you know, but change his or her sex.

9. Write within a min-max word limit: 1000–3000 words.

10. Write from the point of view of a character who is blind.

11. Write from the point of view of a character who is deaf.

12. Write from the point of view of a character who is dead.

13. Write from the point of view of a character who is dying.

14. Write from the point of view of a character who is paralyzed.

15. Write from the point of view of a character who is confronting his/her worst fear.

16. Write without Flashback.

17. In place of Flashback, use Flashforward.

18. Write a piece set entirely in one scene. If flashback or recollection is used, they must relate to the one scene in which the piece is set.

19. Write from the point of view of a character who is severely hyperactive or who is otherwise far too overstimulated.

20. Write from the point of view of a character who talks to himself or herself.

21. Write from the point of view of a character who is trying to justify to a group of people some act that the group considers unjustifiable.

22. Use an unusual setting or environment: a wine cellar; a bomb crater; a drained swimming pool; a burning building; a hot air balloon; a railroad yard; the inside of a cargo plane; a freeway underpass; a vault full of gold bullion; a hotel room, the address of which a S.W.A.T. team has mistakenly been given.

23. Write about one or more characters procrastinating: the act of procrastination is the source of conflict.

24. Write using one or more characters who have an unusual or off-the-wall hobby.

25. Write using one or more characters who have an unusual or off-the-wall pet.

26. Write using one or more characters who have an unusual or off-the-wall obsession.

2009/05/09

Lesen

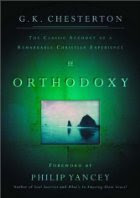

For purposes I cannot fathom, my stack of books to read this summer includes several works of literature that are nearly or more than one-hundred years old.

Herman Melville: "Bartleby" (just finished); "The Bell-Tower"; "Billy Bud, Sailor"

Franz Kafka: "A Hunger Artist" (just finished); "The Great Wall of China"; "The Metamorphosis" (re-reading)

Mark Twain: Life on the Mississippi

Vladimir Nabokov: Invitation to a Beheading

David Rhodes: Rock Island Line

Bill Holm: The Heart Can Be Filled Anywhere on Earth

Bernardo Atxaga: The Accordionist’s Son

J.C. Hallman: The Hospital for Bad Poets (almost finished)

Norah Labiner: German for Travelers: A Novel in 95 Lessons

I find recently that my patience for reading antiquated (if that’s the best word) texts has been improving. A year ago I may have started "Bartleby" but not read to its end. It’s a strange story, mostly interior (character) and reflective. Why doesn’t the narrator just throw Bartleby out of the office? I like how Melville was obsessed with characters in pursuit of unanswerable questions. Nabokov, of course, is a delight to read; what stunning details! seamless transitions! vivid characters! unrelenting precision of narrative! Lolita, Pale Fire, and Pnin all share these traits. I reiterate from a long-ago post: Nabokov is one of the few authors whose long stretches of exposition are a delight to read, and his scenes grab you by your eyelids and don’t let go.

Herman Melville: "Bartleby" (just finished); "The Bell-Tower"; "Billy Bud, Sailor"

Franz Kafka: "A Hunger Artist" (just finished); "The Great Wall of China"; "The Metamorphosis" (re-reading)

Mark Twain: Life on the Mississippi

Vladimir Nabokov: Invitation to a Beheading

David Rhodes: Rock Island Line

Bill Holm: The Heart Can Be Filled Anywhere on Earth

Bernardo Atxaga: The Accordionist’s Son

J.C. Hallman: The Hospital for Bad Poets (almost finished)

Norah Labiner: German for Travelers: A Novel in 95 Lessons

I find recently that my patience for reading antiquated (if that’s the best word) texts has been improving. A year ago I may have started "Bartleby" but not read to its end. It’s a strange story, mostly interior (character) and reflective. Why doesn’t the narrator just throw Bartleby out of the office? I like how Melville was obsessed with characters in pursuit of unanswerable questions. Nabokov, of course, is a delight to read; what stunning details! seamless transitions! vivid characters! unrelenting precision of narrative! Lolita, Pale Fire, and Pnin all share these traits. I reiterate from a long-ago post: Nabokov is one of the few authors whose long stretches of exposition are a delight to read, and his scenes grab you by your eyelids and don’t let go.

Mining for Language

What use can be wrung from the oldest stories collecting digital dust in your hard drive? I have called them "White Whales" because, well, they are an obsession. But I’m not trying to hunt them across the sea and kill them. The metaphor is imprecise. These old stories are those I wrote three or more years ago. I didn’t know what I was doing, I just wrote them. Tackier stories have been written. Stupider stories have been written. But these old stories are awfully tacky and generally stupid: embarrassingly so.

But: they contain weird, interesting stuff. Rough images. Raw voices full of grit and dandruff. Narratives bent at odd angles like girders before a collapse. These are fucked-up pieces of artifice, as gangly and awkward as teenagers. And now, a few years distant, I can see what you were struggling so hard to do back then. You were putting in quite an effort. You had something to prove. Your story, it made no sense. But, wow! Do you see what you did without even knowing it? In those days writing a story was a pursuit, a chase. Words added up to pages and pages of this which was not a story, but something better: a story mine.

A mine, as in "coal mine" or "uranium mine" or "gold mine" or whichever mineral you wish to extract from the narrative earth. Bizarre images jump out among the striated patterns. From another, more recent story, I extracted one entirely new story from a single paragraph of about two-hundred words. That is what I mean by a mine. Much the same way that I read with a pen—–writing down unusual sentences, noting images that catch my attention, reminding myself to look up an unfamiliar word later—–when reading a book, I extract the useful and the strange from my own narratives, things I never noticed before.

Do we all have story mines? I’ve heard that Tobias Wolff throws away every rough draft. Why would he do that? I’ll probably spend the rest of my life dragging around binders of notes and papers wherever I go. Words are up for grabs. I must find them and write them down.

But: they contain weird, interesting stuff. Rough images. Raw voices full of grit and dandruff. Narratives bent at odd angles like girders before a collapse. These are fucked-up pieces of artifice, as gangly and awkward as teenagers. And now, a few years distant, I can see what you were struggling so hard to do back then. You were putting in quite an effort. You had something to prove. Your story, it made no sense. But, wow! Do you see what you did without even knowing it? In those days writing a story was a pursuit, a chase. Words added up to pages and pages of this which was not a story, but something better: a story mine.

A mine, as in "coal mine" or "uranium mine" or "gold mine" or whichever mineral you wish to extract from the narrative earth. Bizarre images jump out among the striated patterns. From another, more recent story, I extracted one entirely new story from a single paragraph of about two-hundred words. That is what I mean by a mine. Much the same way that I read with a pen—–writing down unusual sentences, noting images that catch my attention, reminding myself to look up an unfamiliar word later—–when reading a book, I extract the useful and the strange from my own narratives, things I never noticed before.

Do we all have story mines? I’ve heard that Tobias Wolff throws away every rough draft. Why would he do that? I’ll probably spend the rest of my life dragging around binders of notes and papers wherever I go. Words are up for grabs. I must find them and write them down.

2009/05/03

Further Sideways Process

What seen when pondering a cat. The wishing cat. Here, have an elbow. He elbowed him in the face. [verb: to ELBOW] ‘Fatalism’ is a system of belief in those things which cause death. Scratched out and abandoned to all of one’s money. In this place we try to question every answer; the reward is not money, not cars, not appliances, but hard liquor. *** There are times when I feel unafraid. Other times I feel so afraid it’s all I can consider, my fear. Moaning doesn’t help. Nor does groaning. My fingertips tingle. The cat pretends to sleep though she is actually watching me with her ears. I watch her breathing. I watch with my eyes. Pricks are not prickly. Remember the census. The census! *** I took up the cats’ toy and in a great fury pressed it against my asshole and farted; the toy, a miniature plush moose, was now saturated with fart. I proceeded to present the moose to each of the cats. Each cat sniffed the moose and the fart. I felt vindicated. *** Consider the contra-bassoon. And what of? And what of? And what of? Hammer sledgehammer ballpeen-hammer hammertoes drop-forged hammer hammerhead hammerheart lunghammer hammer to the guts Hammer-Smashed Face Imbibe the stomach Drink the stomach Drink it! A racoon bears fangs grinning. It knows something delicate but you can’t tell what no matter how long you squint A racoon just knows and eats your tossings your uneaten and scatters the rest for her offspring. *** People made him nervous. Unreasonable people who interrupted his reverie during lizard-feeding time were in particular prone to make him nervous. He kept a gila monster in a fifty-gallon terrarium with a heat rock and a little cave made of stones. The gila monster feasted on eggs. *** Miniature ampitheaters. In this place dwelt a live scorpion, a black one with enormous fat pincers. It rarely moved. *** An indoor herb garden. We raised parsley, rosemary, and grass of a sort meant to be eaten by the cat, though she avoided the grass and instead waited until we dropped collard greens or lettuce on the floor. *** Abandoned caboose. Hands always feeling about. *** Have you ever driven through a town after a tornado had hit? Like a couple days after, when people are out trying to clean up, but they don’t have any heavy equipment yet, and it doesn’t look like they’re really doing anything but standing around? *** Decorum? *** Unhook your eyes from my chest, please.

2009/05/02

Twitchiness and Nonretention

At this link is a series of charts showing how Twitter can't retain its users. Which I think is apt and funny. What is it, an average of 20 to 40 words per "twitch"? It is called a twitch, right? If not, it should be. Twitter has all the makings of a speed-addict's flightiness, little bursts of information regarding what a person is doing at a particular moment. In truth, each and every twitch implies the act of typing out the twitch itself. For example:

I am staring at Einstein's hair! [I am typing this message] Why am I going on and on about this?

2009/05/01

Exclamation: !

At this link, a British guy discusses exclamation marks and other punctuation.

What do you think of exclamation marks? Should they, as Elmore Leonard apparently prefers, appear no more than once or twice per 100,000 words of prose? I beg to differ. I love exclamation marks. When used at precisely the right moment, an exclamation mark makes all the difference in rhetorical and/or emotional effect. Exclamation marks convey desparation in a way no other punctuation can. The lesson is use exclamation marks but not to excess!

What do you think of exclamation marks? Should they, as Elmore Leonard apparently prefers, appear no more than once or twice per 100,000 words of prose? I beg to differ. I love exclamation marks. When used at precisely the right moment, an exclamation mark makes all the difference in rhetorical and/or emotional effect. Exclamation marks convey desparation in a way no other punctuation can. The lesson is use exclamation marks but not to excess!

What Are You Talking About?

question,

reading,

subcutaneous punctuation,

writing

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

A Slowly Growing List of Things to Look Forward To When You Have a Child

- Every day is either Christmas or Halloween or Birthday or Easter

- Leave those cats alone! They're going to scratch you and it will hurt

- You cannot lie under circumstances, but nor can you tell the literal truth

- Geez that kid is sharp

- Can I have cake? Can I have cake? Can I have cake? Huh? Daddy? Can I have cake?

- For the last time, stop asking me!

- Noticing the growth: taller and a bit heavier to carry

- Children's television shows

- Food. Wasted food

- Remembering that you once acted this way yourself

- Watching where the both of you are going

- The joy of hearing the word "fuck" being used experimentally, and justifying this experimentation by saying "Well they learn it eventually"

- TANTRUMS

- Sitting down together on the living room floor, a mess of blocks & cars & plush Care Bears strewn around you, discussing the complexities of each car's identity, its name, and why it is so humorous

- Having to take responsibility for someone else for a change

- More frustration than you're prepared for

- Wicked cackling

- Drawings of potato guys

- Learning about the world all over again

- Circular Logic

- Unexpected hugs and words put beautifully together out of context

- Waking up after 4 hours of sleep, and unexpectedly having to confront shit, in more than one place, including the carpet, a big toe, a butt, a bed, a toilet seat, and underpants